International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

This post provides a brief history of the development of the International Day for the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination and its associated UN treaty The International Convention on the elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (ICRED).

We provide a real life example of the treaties prohibition of discrimination impact in the forthcoming ‘Hate Crime and Public Order Act (Scotland) 2021’ (HCA).

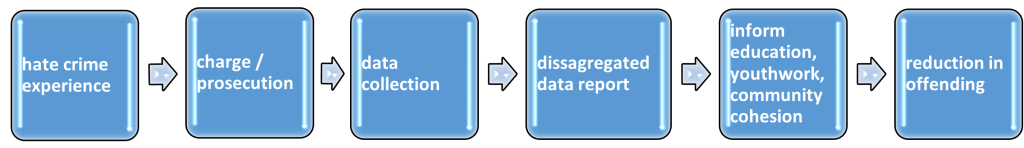

Our ambition is that by tracking trends and publishing disaggregated reports we can reduce the numbers of victims and offenders.

Between 2015 – 2021 there have been 32,251 racially aggravated hate crimes in Scotland. In the same period there have 4,597 religiously aggravated hate crimes.

History of the Day and Treaty

The 21st of March marks the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

The day was initiated by the United Nations in response to the Sharpeville Massacre in apartheid South Africa that occurred on the 21st of March 1960.

69 Black South Africans were shot dead by the Police at a protest against anti-Black Pass Laws that codified apartheid into everyday life.

In addition on 21 December 1965, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) was adopted in the United Nations General Assembly in plenary session by 106 votes to none

The treaty was based on the 1963 resolution in response to Sharpeville adopted by member states outlining that they were,

“Resolved to adopt all necessary measures for speedily eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms and manifestations, and to prevent and combat racist doctrines and practices in order to promote understanding between races and to build an international community free from all forms of racial segregation and racial discrimination”[1].

As such the content of the treaty reflected the ambitions of all member states and crucially adopted a definition of racial discrimination that could be applied to the varying demographic and colonial legacies particularly of western nations.

“1. In this Convention, the term “racial discrimination” shall mean any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life”[2].

Subsequently article 4 of the convention places obligations on the state to prohibit racial discrimination on the provisions outlined in article 1.

The prohibition includes the ‘dissemination of ideas’ that promote violence, incitement to violence or racial superiority.

Article 4 has been integrated into Scottish criminal law for a number of decades and reflects the provisions outlined in article 1 of the convention.

As such racial aggravations are prosecuted in Scotland in relation to incidents that pertain to the racial hatred of someone’s colour, nationality, ethnic or national origin. These definitions are contained fully within the Hate Crime and Public Order Act (Scotland) 2021.

Article 5 of the treaty goes onto outline economic, social and cultural (ESC) rights pertaining to health, education, cultural recognition, housing, social security and participation. ESC rights help people and communities to flourish and fulfill their potential.

Tackling hate crime, health, education, culture, housing and aspects of social security are devolved powers to Scotland. Thus, the Scottish Governments obligation to comply with the CERD treaty exists across many areas of life and public service provision.

It is often a critique of international human right law that it remains distant from everyday life.

Yet, in the example of CERD we can specifically identify examples where the legacies of international consensus post WW2 and the Sharpeville massacre apply in Scotland in our day to day lives.

[1] United Nations – International Day against all forms of racial discrimination – https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-racism-day

[2] UN General Assembly, International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, A/RES/2106, UN General Assembly, 21 December 1965, https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/1965/en/16622 [accessed 21 March 2024]

The example of the Hate Crime and Public Order Act (Scotland) 2021

Hate crime aggravations in relation to race and religion in Scotland have a multi decade history in Scots criminal law.

In the case of the consolidation exercise carried out by Lord Bracadale to make laws pertaining to hate crime simpler to understand and access both race and religion were uncontroversial.

In order to enhance society’s capacity to respond to the issues of racial and religious aggravations BEMIS successfully campaigned for the incorporation of a data disaggregation duty[1], contained within section 15 of the act to bring Scots criminal law further into compliance with the International Convention on the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination.

[1] BEMIS Submission to Justice Committee July 2020 and Hate Crime Bill Scrutiny.

Available here: https://bemis.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Hate-Crime-and-Public-Order-Scotland-Bill-BEMIS-July-2020.pdf

“BEMIS Scotland call for a legal requirement to be integrated into the Bill that places a duty on the Scottish Government, Police Scotland, and any other relevant duty bearers to develop a bespoke system of Racist and Religiously aggravated hate crime data collation and disaggregation. An integration of data collation and disaggregation as a legal requirement would ensure that Scotland’s institutions were operating in compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination and provide society with a much clearer picture of the nature and prevalence of the different types of racism that manifest in Scotland on a daily basis on the grounds of religious hatred or colour, nationality, ethnic or national origin”

In 2016 the international committee on the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination, a body of independent, international experts instructed Scotland to create a system that would enable the Scottish Government and Police Scotland to publish annual disaggregated reports on the specific nature of racially aggravated hate crime in Scotland[1].

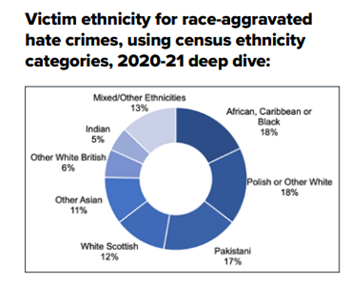

For example, what this means in practice is that instead of being told there were 4,172 race hate crimes in Scotland in 2019/20[2] we will be able to know exactly what protected racial provision was targeted.

The protected racial provisions contained with the Hate Crime Act mirror Article 1 of the International Convention on the elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination covering, Colour, Nationality, ethnic or national origin.

Thus if it is African, Black, Pakistani, Irish, Gypsy Traveller, Polish or whatever ethnic group is experiencing racially aggravated hate crime we will have real time, detailed annual statistics to inform policy.

The longer-term policy ambition is to instigate and inform non judicial interventions in education, youth work, cultural celebrations, community cohesion that respond to emerging evidence on racially aggravated hate crimes in doing so significantly reducing the numbers of offenders and victims.

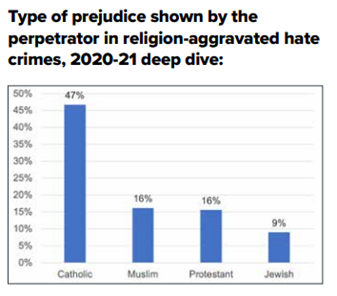

The same process will inform work to respond to the intersectional issue of religious aggravations.

In Scotland, Catholics, Muslims and Jewish people face significantly disproportionate levels of religious aggravations which are often conflated with ethnic identities.

Jewish ethnicity can capture both a religious and cultural identity. In Scotland for historical reasons of migration, perception and lived experience Catholic / Muslim have been used as indicators of Irish[3] and Pakistani ethnicities.

As an interim measure while the Scottish Government and Police Scotland worked towards setting up the systems required to appropriately capture the nature of racially and religiously aggravated hate crimes they have conducted deep dive exercises to capture trends in ongoing hate crime experiences. The deep dive exercise involved Scottish Government justice analysts reading through 2000, 30% of all hate crime related police reports in the period covering 2020-21 and extracting from these the nature of the aggravation.

[1] 2016 Concluding observations on the twenty-first to twenty-third periodic reports of United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – Available here: https://idsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/CERD_C_GBR_CO_21-23_24985_E.pdf

CERD/C/GBR/CO/21-23, para. 16 – (b): the state party should ‘Systematically collect disaggregated data on hate crimes, ensure that measures to combat racist hate crimes are developed with the meaningful participation of affected groups, and undertake a thorough impact assessment of the measures adopted to ensure their continued effectiveness’

[2] Excel additional document sheet. Table 6 – Available here: https://www.gov.scot/publications/updated-study-characteristics-police-recorded-hate-crime-scotland/documents/

[3] The 1923 Menace of the Irish Race to the Scottish Nation outlined in highly racialised language the problematic nature of Irish ethnicity. It was not until 2001 that people could record their ethnicity as Irish in the Scottish Census.

“The Irish cannot be assimilated and absorbed into the Scottish race. They remain a people by themselves, segregated by reason of their race, their customs, their traditions, and, above all, by their loyalty to their Church, and gradually and inevitably dividing Scotland, racially, socially, and ecclesiastically”.

While the significantly disproportionate levels of incidents targeting Black, African, Pakistani, Indian, Polish, Catholic, Muslim and Jewish people and communities came as no significant surprise it is nonetheless critical to archive, recognise and strategically respond to evidence in an informed and targeted way.

Enhanced compliance with the CERD treaty will mean that data collection is completed at the time of recording the incident / crime and that emerging trends can be tackled proactively in non-judicial settings with an ambition to reduce criminal proceedings.

Hate Crime Strategy for Scotland – Published March 2023. Table on Pg. 14 + 15 available here: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2023/03/hate-crime-strategy-scotland2/documents/hate-crime-strategy-scotland-march-2023/hate-crime-strategy-scotland-march-2023/govscot%3Adocument/hate-crime-strategy-scotland-march-2023.pdf